The Weeping Camel

(Interview with Luigi Falorni, director of 'The Weeping Camel', by David Stratton ...)

LUIGI FALORNI: It all started from the music ritual, which is performed every now and then when a camel mother rejects her newborn, to convince her to accept it again. That was the starting point of the whole project. And that was also what got me interested in making the film.

I was never interested or specialised in doing ethnographical films or strictly ethnographical films. So what interested me about this story was more its general or universal aspect, which is the story of a salvation, basically, of the loss of love and how about a pretty peculiar way to win love back.

We decided from the very beginning to go for a mixture of strictly documentary observing on one hand, and also re-enacting on the other hand. We developed a fairly detailed script and went looking for the story that we had written, basically, in Munich, on a desk.

So we went two weeks researching for the family that would fit to our story and tried to find the family that would be the closest to our ideas. But then again, the family would be slightly different so we would adjust the story to them and we would adjust the story and the script to everyday occurrences - whatever happened that was slightly different or, you know, completely different from what we expected, trying to integrate it in the story. So it was a growing together of the script on one side and reality on the other.

DAVID: But is seems like an incredibly risky thing to go all that way to make a film about something that might not actually happen.

LUIGI FALORNI: Absolutely - I believe the only chance that we could do this film was through a film school because we had the possibility, you know, to take the risk and eventually come home without a film. I don't think any normal production company would've taken the risk.

Review by Margaret Pomeranz

A family of nomadic shepherds in the Gobi Desert use a traditional musical ritual to try and save the life of a rare white baby camel after it is rejected by its mother.

Byambasuren Davaa is the granddaughter of Mongolian nomads. She attended the Munich film school where with fellow student Luigi Falorni she devised, co-wrote and co-directed their graduation film, a story that reaches back to her roots

It's 'The Weeping Camel' set in the Gobi desert it follows the daily lives of four generations of nomads living in three yurts as they wait for the annual birthing of baby camels.

When a rare white camel is born after a long and painful birth the mother rejects the colt, to the quiet despair of the family.

This so-called narrative documentary has a rhythm and beauty to it that fits with the ethnographical nature of its subject matter so that it's hard to know where the documentary ends and fiction begins.

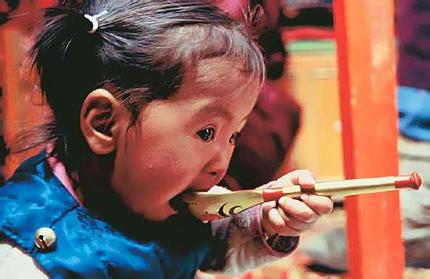

The actors are real nomads who played out their daily lives before the camera, with some re-enactments for the filmmakers. They are delightful, beautiful people, especially young Ugna who practically steals the film from the camels.

The style of direction, simple still shots, reflects the lives depicted. And the landscape is stunning.

David: A film school project? I mean, it's extraordinary, isn't it, really?

Margaret: Yes.

David: Because there was such courage to go out there with a limited amount of film stock and shoot this. It was shot on 16 mil, I think, and it was just marvellous that they managed to capture this drama. And the thing about these fly-on-the-wall documentaries is you never know in which direction the narrative's going to take you. And luckily for them it's a wonderful story. The camels are amazing actors.

Margaret: Aren't They

David: They're so vocal.

Margaret: I know! Who would've thought we'd be entranced by camels?

David: I know. They're great. But as you rightly say, the little boy is also amazing because his journey, when he goes for the first time outside this enclosed community to a bigger community and discovers the world outside, things he never knew about, sort of like Wide-eyed. It's an amazing thing. I love this film. I think it's really great.

Margaret: So do I. 4 stars from me.

David: Yes, and 4 from me too.

Tom Ryan, The Sunday Age, July 2004

The Weeping Camel, co-directed by Mongolian Byambasuren Davaa and Italian Luigi Falorni and set in the Gobi Desert in South Mongolia, the camera watches unobtrusively while an extended family of shepherds go about their business, raising their young and looking after their flock, which includes a herd of camels.

The result is one of the best films I've seen this year, an emotionally stirring depiction of a culture that couldn't be further from our own and which, in its close-to-nature way, seems far more in touch with the things that really matter. At its heart are the rituals that sustain the shepherds and the sense of mission that binds them. But, finally, everything hinges on the shepherds' efforts to heal the rift between a camel and the albino newborn that she has rejected.

Reviewer Philippa Hawker, September 30, 2004

A taste of nomadic life.

A story of four generations and two camels, a tale of tradition and modernity, a work of slow-moving charm, The Weeping Camel is set in the Gobi Desert of Mongolia. It tells the story of a nomadic family, the challenge that it faces one spring and the singular solution to its problem.

Written and directed by Mongolian filmmaker Byambasuren Davaa and Italian filmmaker Luigi Falorni, the work was their graduation project from the Munich Film School.

The film spends time establishing characters, relationships and location, as family members go about their business and await the arrival of additions to their camel herd. One birth is straightforward but another, a spindly white baby, emerges after a long and painful labour. The mother rejects it, refusing to allow it to suckle. Family members use all kinds of strategies to try to persuade her, but decide they will have to seek help.

Two boys travel by camel to a nearby town to bring back someone who can help. The younger of the two - wide-eyed, eager, aware that he has things to learn - is both actor and observer in the movie, and his journey of discovery is linked with that of the audience.

We are already aware of the incursions of the world beyond the desert. The boys are sent to bring back a man with traditional (albeit unexpected) skills, but they are also charged with the task of bringing back new batteries for a radio. And the closer they get to town, the more aware they become of the talismans of consumption: satellite dishes, TV, motorbikes, objects of desire that the young boy longs to see in his own home.

The Weeping Camel is a beguiling film with the texture of a documentary. Its cast members - from great-grandparents to toddlers - play themselves, doing what they would do in their daily lives, but in front of the cameras.

The film records routines, rituals and daily life within a story that the filmmakers devised.

Falorni has described this as narrative documentary, a term that does not quite acknowledge the elements of performance and the scenarios that the film must necessarily contain, no matter how authentic the behaviour in front of the camera.

Review by Bernard Hemingway

Synopsis: In the Gobi Desert in Southern Mongolia, a small population of herders prepares for their female camels to give birth to young colts. The last colt of the season is a hard delivery for a novice mother, who rejects her troublesome offspring, leaving her owner's family the task of reconciling her to her new role.

If you've ever seen the classic 1934 Robert Flaherty documentary Man of Aran, about a family eking out a rudimentary existence on a bare and tiny island of the coast of Ireland you will readily find comparisons with this film. Flaherty came under criticism for having staged some of his scenes but in this context that only brings the two films closer together. The Story of the Weeping Camel, which makes no pretence to be a documentary, shares with Flaherty film the subject of survival in a harsh environment. It has gentler feel and the main elements are wind and sand rather than wind and sea but there is a similar observational attention (and a very similar use of spare dialogue and ambient sound) to the daily round of activities and the rhythms of its subjects' lives.

An impressive achievement by two Munich film school students, it is beautifully photographed and skilfully constructed, deftly using the frame of its simple story to show us another way of living, one which one cannot help but feel is not likely to last much longer in the face of the attractions of television and video games on the young. Of course as Westerners we are very distant from the realities of its world and how true to the herders' lives or otherwise it is cannot be said although as co-director Davva is a native of Mongolia one assumes there is not too much Flaherty-like manipulation. Ultimately The Story of the Weeping Camel has won audiences because its central message about family and community is one to which we can all relate, whatever culture we belong to.